Brendan’s Personalized Fasting Diary

Giving Me Back the Control of My Health and Weight with

‘Reduced Frequency Eating’

The concept of control over food and ultimately our weight is something that probably seems almost impossible to most people in our modern, abundant society. For millennia our bodies have evolved to allow us to survive when food was scarce. Humans have developed complex biological processes that efficiently store any excess food (during feast) as energy to be utilized later in the absence of food (during famine). However, these processes that have helped us survive into the new millennium are now working against us in our modern society, when energy-dense food is abundant and physical activity is largely unnecessary.

The most obvious biological process that is now working against us is our ability to extremely efficiently turn food into stored energy. Any excess food, whether is starts out as carbohydrates, protein or fat can be stored in the body as different forms of energy to be utilized later. In times of famine, the body can then turn all these forms of stored energy into fuel to power the body’s most basic functions - prioritizing the brain. Most of us will be well aware that fat is our most efficient energy storage system however it is this same storage system that most of us are trying to control.

Traditional Restriction Diets

No matter how hard we look for potential solutions to cheat the system, if we get the energy balance wrong and consume too much food or don’t burn off enough energy, we will store this excess energy for future potential famine. Many theories have been proposed about restricting certain macronutrients (e.g. Atkins, Dukan), foods from certain regions (e.g. Mediterranean) or eras (e.g. Paleolithic), eating at certain times of the day (time-restricted fasting) or alternate days (e.g. alternate-day fasting), but in the end if total calories consumed are greater than calories burned, your body will be able to store the excess energy. Most of the claims for these traditional diets seem to defy logic, but the results don’t. Looking at all the research, testing diets in both clinical settings and the real world, the science confirms that there is no one diet that has been consistently shown to be better than any other in helping people lose weight.

One classic randomized trial compared a range of popular restriction diets including Atkins (low carb), Ornish (low fat), Weight Watchers (reduced portion/calorie), and Zone (low glycemic index) diets. Results showed that both compliance to the diet and weight loss were rather disappointing. Weight loss at 1 year was 4.6lb for Atkins (53% of participants completed the diet), 7.1lb for Zone (65% completed), 6.6lb for Weight Watchers (65% completed), and 7.3lb for Ornish (50% completed) (Dansinger, Gleason, Griffith, Selker, & Schaefer, 2005). The authors concluded that each popular diet “modestly reduced body weight and several cardiac risk factors at 1 year and that overall dietary adherence rates were low”.

Despite no studies conclusively showing that any style of diet is better than any other, most clinically studied diets do show that you can lose some weight on traditional restriction diets. A summary of weight loss research in 2014 shows that with a range of weight loss strategies, dieters are able to lose a modest amount of weight and keep it off (figure 1). With exercise alone you might be able to lose around 3lb, however a more successful strategy is to focus on diet and then on average you are able to lose around 10lb. Combining diet and exercise has been shown to be an even more effective strategy. Looking for a pharmaceutical solution to the problem was a very 1990’s strategy and despite the ability to lose some weight, ask anyone about the side effects of Orlistat (which reduces your fat absorption) and you might reconsider this option.

Figure 1: Average weight loss according to different strategies—a meta-study of clinical trials (Look AHEAD Research Group, 2014)

Some people would love to lose 10lb of weight and keep it off, however most people have a desire to lose more and sometimes for health reasons they need to lose a lot more - the majority of adults (55%) who are dieting to lose weight have a goal of losing 20 lbs or more (Mintel). “Specifically, among those trying to lose weight, the average weight loss goal is 35.5lbs” (Mintel, 2017). The problem with most traditional restriction diets is that because they are so regimented and restricted, it means they are difficult to sustain over the long term as shown by the low compliance rates. Most of these traditional restriction diets restrict you from eating certain foods, with the most popular in the last decade or so restricting carbohydrates (e.g. Atkins or Dukan diet) or some even more specifically sugar.

While reducing refined carbs or sugar in most of our diets is a good idea, and for some people this is an extremely effective weight loss strategy, the ability to constantly resist temptation in our abundant society is nearly impossible. Some people may have the willpower to maintain these diets for a few months to a year, but there are not many people that will say that it is sustainable for the rest of their lives. These traditional restriction diets cannot simply be incorporated into the real world so they turn into a six month short-term diet and then you struggle to maintain the weight lost.

So if you are looking to lose more than 10lb, you are going to have to look beyond the traditional restriction diet and exercise strategy that has been promoted for the past 30 years. You are going to have to find other strategies that can become sustainable over a longer timeline. You are going to have to find a way of eating that fits with your biology and your lifestyle.

Traditional Fasting Diets

Traditionally it has been assumed that all humans handled food in the same way. If scientists were able to optimize the foods and therefore the nutrients we consumed, we could find the optimal diet for our entire species. However, through personalized nutrition we are learning, that in fact there is genetic variation in how we all process food and an optimal diet for one person may not be optimal for another. Therefore, flexibility to learn and understand what foods and nutrients are best for each individual is preferable to one-size-fits all, traditional restriction diet that removes certain foods from our diet.

The constant 24/7 willpower required for traditional restriction diets is the reason that fasting diets have become more popular in recent times. While you are restricted from eating at certain times, when you are able to eat you have the flexibility to eat what you want or what your body is telling you that you need. The most popular style of fasting diet is called alternative day fasting and involves eating only 25% of your regular energy intake one day (fasting day) and allowing 125% of your regular energy intake on the next (feast day). The other fasting diet is time-restricted fasting where you only eat for an 8-hour period during the day (normally from 10am-6pm).

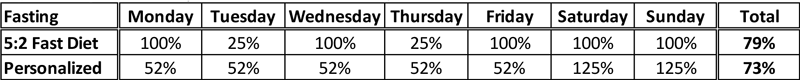

Despite the flexibility for the types of food you can eat, these fasting diets are still regimented and restricted in terms of the days and times that you can eat. The ‘5:2 Fast Diet’ was the first diet to provide a bit of flexibility in terms of splitting the fasting days over the week. While you fast for 2 days, you then eat normally for the other 5 days of the week.

While we all know that as humans, we are all very different, why are we still trying to find a single diet that suits everybody? These one-size-fits diets don’t provide the kind of flexibility and personalization, we expect in the rest of our lives. This is why diets are only a short-term fix, because they are just not sustainable over the long term. Why are we not personalizing eating to our tastes and preferences so that a lower calorie lifestyle can become a way of life? Why is there not an easier way to get back the control of our health and weight?

My Personalized Fasting journey

My mum would call it ‘puppy fat’, which is supposed to be an endearing term for ‘fat on the body of a baby or child which disappears around adolescence’. However, I was always conscious that I was taller but also a bit fatter than the other kids. This larger size helped me in some sports, but it was not until a mistimed comment from an extended family member that I became motivated to try to be a more ‘normal’ size.

The teenage years are the hardest for self-consciousness and why mistimed comments can have a much larger impact than intended. But as a result, at the age of 14 I joined a gym despite advice that weights at that young age can affect normal growth. The increased exercise worked for me and I was able to maintain a healthy weight until the end of high school. That is, until I discovered social drinking.

Leaving high school at 172lb (at 6’1” this was a BMI of 22.7 and right in the middle of the healthy range), I have always struggled to keep my BMI in the healthy range below 25 (or below 190lb) since. Poor nutrition and excessive drinking during college didn’t help. However due to my higher than normal consciousness of weight (set at a very early age), I never let my weight get too much above 185lb.

As I imagine happens to a lot of us however, something changed when I reached 30. I took a year off work to undertake my MBA at the University of Oxford in England. With a return to the excessive drinking and a lack of exercise due to study, I ballooned out to over 200lb (BMI of 27) and was no longer the healthy person I had been my whole life.

At the end of my study in 2011, my wife and I returned to New Zealand and I decided to retake control of my weight. Returning to work, I was once again in a routine to be able to start regular exercise. 2011 was also the year that the Dukan diet (removing carbs and fat from the diet) was extremely popular and I decided to try it out. I love meat and dairy, and it is easy to get high quality, low cost protein in New Zealand, so this diet worked really well for me and I was able to get back down to my previous 185-190lb weight. Ultimately however, the diet was not sustainable for me due to the restricted nature of the diet, but I was able to keep off any extra weight gain through exercise (up to 5 times a week) and removing snacking from my diet during the week.

Looking at the research

Reading the latest scientific articles, it quickly became clear that there is no consensus in the academic world about the longer term sustainability of traditional diets. And there is certainly no evidence that any one traditional diet is better than any other based on clinical evidence despite their popularity. It appears that the only consensus that can be reached by health experts is that ‘making lifestyle changes – including following a healthy eating pattern, reducing caloric intake and engaging in physical activity – is the basis for achieving long-term weight loss’ (National Institutes of Health, 2015).

I was already engaging in physical activity up to 5 times during the week when work allowed and very rarely less than 3 times a week. I also ate reasonably healthily and didn’t want to restrict my diet anymore based on the traditional restriction diets, which I had tried before with the Dukan diet. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, I made the decision that to make any dietary changes sustainable for me, I was unwilling to sacrifice my social life or my social drinking in the weekend. Therefore, the only lever I had to make a change in my lifestyle was to reduce my calorie intake. Research into the calorie restriction needed for weight loss, it appears you need to reduce your weekly calorie intake to approximately 75% of your normal calorie intake to be effective.

Personalized Calorie Reduction

I knew from the start that a regular calorie-reduced diet would not work for me. As can be seen in figure 2, I know that I just don’t have the willpower to be able to stick to a diet that is 24/7 (similar to the portion and calorie restriction of a Weight Watchers type diet). I am very social in the weekend and tend to overeat during these two days, while I have much more self-control during the week.

Figure 2: Regular calorie-reduced diet. Calorie reduction required over the week to lose weight

I found a diet that appeared to suit me a lot more. The 5:2 Fast Diet has been extremely popular in the UK, while not quite so popular in the US. At its most basic, it involves 2 days of fasting (eating a controlled number of calories - 500 calories for women and 600 calories for men) and 5 days of eating ‘normally’. I liked the concept that I would only have to be consciously dieting for 2 days and enjoying life for the rest of the week. It was the first traditional diet to split the calories out into a ‘weekly calorie intake’, which seemed to make sense to me and fit into my way of living.

So I started to do some research into the diet and found that there was very little clinical research into the 5:2 Fast Diet. However the original advocate of alternative-day fasting was a researcher in the US by the name of Dr Krista Varady from the University of Illinois with her ‘Every Other Day Diet’. She was doing a lot of research into alternate day fasting, which over the week gives exactly the same calorie reduction to a regular calorie-reduced diet (figure 3).

Figure 3: Alternate day fasting. Calorie reduction required over the week to lose weight

The key idea of the diet is to reduce calories to 25% of regular calories on one day (fast day) and ‘eating anything you want and all you want, every other day’. Feast day was estimated to be 125% of your normal calorie intake. The average of the two days would give you the same overall calorie reduction as a regular calorie-reduced diet. “Alternate-day fasting has been promoted as a potentially superior alternative to daily calorie restriction under the assumption that it is easier to restrict calories every other day” (Trepanowski, et al., 2017).

However in a gold standard weight loss trial published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in May 2017 comparing the alternate-day fasting diet versus regular daily calorie restriction, “Alternate-day fasting did not produce superior adherence, weight loss, weight maintenance, or cardioprotection versus daily calorie restriction.

Rather, it appears as though many participants in the alternate day fasting group converted their diet into de facto calorie restriction as the trial progressed. Moreover, the dropout rate in the alternate-day fasting group (38%) was higher than that in the daily calorie restriction group (29%) and the control group (26%). It was also shown that more participants in the alternate-day fasting group withdrew owing to dissatisfaction with diet compared with those in the daily calorie restriction group. Taken together, these findings suggest that alternate-day fasting may be less sustainable in the long term, compared with daily calorie restriction, for most obese individuals. Nevertheless, it is still possible that a certain smaller segment of obese individuals may prefer this pattern of energy restriction instead of daily restriction” (Trepanowski, et al., 2017).

Because alternate-day fasting diet did not produce superior results than regular calorie-reduced dieting, it looks like it comes down to personal preference and whether alternate-day fasting fits into your lifestyle and preference for dieting every other day. I decided that alternate-day fasting would not suit my lifestyle as it would mean that at least one day of the weekend, I would need to be fasting and it just wouldn’t be sustainable for me. I liked the idea with the 5:2 Fast Diet that I would only have to think about dieting 2 days a week. Comparing the three diets, while the calorie reduction wasn’t quite as high for the 5:2 Fast Diet, therefore it would take longer to lose weight, I decided to try it.

Figure 4: Comparison of the 5:2 Fast Diet to alternate-day fasting and calorie-reduced dieting

Of all the diets that I have heard people participate in, I have heard much better feedback about the 5:2 Fast Diet and the ability for it to be sustainable for initial weight loss and then ultimately weight management. I started by reading Michael Mosley’s book ‘The Fast Diet’ and it gave some great context around the benefits of fasting. While some of the medical claims were a bit radical for me, it talked about the mental clarity (and sometimes euphoria) that people experience while fasting, so I was very interested to try it. It also gave me the context to understand that people can do days, if not weeks fasting. Surely, I would be ok for a day with only two small meals.

And I was. I have to admit that it wasn’t easy, but I did quite enjoy the challenge. It did make me realize however that I had forgotten what it felt like to be hungry. I didn’t quite feel the euphoria that some people talk about with fasting, but surprisingly I did enjoy a feeling of mental clarity and certainly did not feel faint or dizzy. I managed the hunger pangs by experimenting with supplementation and I was able to find some products that work for me. In the end trying the 5:2 diet was transformative for me. Despite being difficult I did feel the benefits of fasting for myself, and I was converted.

Personalized Fasting

So for some who try it, the 5:2 Fast Diet will work for them and they will have no need to personalize their fasting further. However, an important part of the 5:2 Fast Diet is that ‘success also depends on not over-eating on your normal days’. And for me I found I was still eating too much on the weekend, and liked the alternative-day fasting idea of being able to not have to worry about what I was eating at some time during the week. And it looks like this is a common perception - according to Mintel research, for most people, committing to a long term diet is difficult and “in order to satisfy consumer’s desire to treat themselves, diet plans that account for ‘cheat’ days could produce more long term success” (Mintel, 2015).

Therefore using the 5:2 Fast Diet as a base, I decided to personalize my fasting. The first (and easiest decision) was to make the weekend ‘cheat days’ – this means I have two days when I don’t have the think or worry about food or drink. Considering this decision, I then had to conduct 3 ‘fasts’ during the week.

Figure 5: My first attempt at Personalized Fasting

This personalization did mean that I did reach my calorie goals for the week (75% of normal intake), but I was still struggling with reducing calories to 25% on the fasting days. On the 5:2 Fast Diet, the suggested method to reduce your calories (to 500 for women or 600 calories for men) is to take 2 small meals over the day – a regular breakfast and then a small dinner. There are now whole cookbooks that help you achieve the calorie requirement of the 5:2 Fast Diet, but still the diet wasn’t working for me. It was hard work, even with Calocurb’s support, I was very hungry towards the end of the day and I felt like I was missing out on a full social dinner with my family.

So I started to experiment with spreading the ‘pain’ of fasting over the course of the week. Personally, I found being ‘good’ during the week easy and the fact I didn’t have to worry about my calorie intake during the weekend was always reassuring and certainly a treat for being good during the week. Spreading the calories over the week also made the daily calorie goal seem much more achievable.

Figure 6: My second attempt at Personalized Fasting

So now that I had my daily allocation of calories sorted for the week, I now had to figure out how to effectively halve my regular calorie intake during the week. Having done some testing with the 5:2 diet, I found that I personally needed breakfast to kick-start my day and I didn’t seem to miss lunch that much (with the help of Calocurb). I was certainly hungry by the time I got home and this is where I found that reducing calories to 25% didn’t work for me. After a small fasting size dinner I was still hungry. The other benefit with skipping lunch is that I would be saving up to $50 a week on lunch costs.

So I started to investigate the split of when calories were consumed during the day and what I found seemed to make sense. Based on American nutrition surveys, the daily split of calories is shown in figure 7. The 24% of calories that are consumed as snacks was simplified into a morning, an afternoon and an evening snack. I have to be honest that I was surprised that an evening snack existed but apparently 67% of Americans have an evening snack, it was around 15% of their total daily calorie intake and was eaten about 8:20pm, 2 and half hours after dinner.

Figure 7: Meals where calories are consumed in America (Kant & Graubard, 2015)

The first personalization decision I made for myself is that dinner is my most important meal of the day due to being a treat at the end of the day and it is also a very social meal for me personally. So I didn’t want to sacrifice any calories here. This left me with 19% of my calories to be spread over the rest of the day. For me it was an easy decision to lose the snacks (which I was already doing), which left me in an interesting position of a choice between breakfast and lunch.

You will see research and advantages of skipping either lunch or skipping breakfast. But in the end, it is personal. For me I learnt through my 5:2 Fast Diet research that I prefer the routine of breakfast and it saves me time and money at lunch. So my decision to skip snacks and lunch left me with the equation seen in figure 8.

Figure 8: My personalized dairy calorie consumption on weekdays

By personalizing my eating I was now only consuming 52% of the regular calorie consumption during the week. This left me with approximately the 25% weekly calorie reduction that is recommended in the research for weight loss (figure 9). However now my way of eating was personalized to my preferences and I knew would be sustainable for me over the longer term. And I still had my cheat days in the weekend.

Figure 9: My third attempt at Personalized Fasting

Having started to discuss Personalized Fasting with people, one of the most popular alternative preferences is for people who don’t feel hungry in the morning and therefore are happier skipping breakfast than lunch.

Figure 10: Calorie reduction when breakfast is skipped

While this doesn’t quite give as much calorie reduction as with skipping lunch, it is still a 20% calorie intake reduction over the week and the same weekly calorie reduction as the 5:2 Fast Diet. This is also a similar eating regime to the time-restricted fasting diet that has been popularized by the ‘8 Hour Diet’.

Figure 11: Weekly calorie intake when skipping breakfast during the week

Even though I was now eating more than double that amount of food compared to a 5:2 fasting day, I still seemed to be reaping the benefits of the fasting days (mental clarity and weight loss), without as much pain. So I started doing some research into why eating only twice a day during the week was so beneficial for me.

Reduced Frequency Eating

Larger portion sizes are frequently blamed for the growth in the obesity epidemic and indeed portion sizes have increased over the past 40 years (Duffey & Popkin, 2011). But “despite pervasive commercial trends toward large portions, there is surprisingly little compelling evidence that these are causally linked to obesity” (Livingstone & Pourshahidi, 2014). So despite the fact we have been eating larger portions it appears that this hasn’t been the key contributor to people putting on weight.

In fact it has been shown that the obesity epidemic can be more closely correlated to increased eating frequency than it can be to increased portion sizes (Mattes, 2014). However the conventional dietary advice focusses on the consumption of small, regular meals. There are whole dietary systems based on the concept of ‘eating six meals a day to keep your body running and help fight off hunger’.

Looking at the research it appears this recommendation was based on flawed 50 year old observational studies that relied on self-reported dietary intake. This type of research has long been confirmed as unreliable. More recent research in controlled intervention trials, have shown little or no beneficial impact of increased meal frequency on body weight and health during weight maintenance or weight loss (Hutchison & Heilbronn, 2016). In fact over the past 30 years, the frequency of eating for the median American increased from 3.5 times per day to 5 times per day, a change that was accompanied by an increase of 400 calories per day (Duffey & Popkin, 2011). Despite larger meal portions it appears that in evolutionary terms this is not as big an issue for our bodies as increased eating frequency. Maybe our bodies really are adapted to and prefers feast and famine.

Also considering the fact that chips, biscuits, ice cream and confectionery dominate US snacks sales (Mintel), it is no surprise that as the frequency of snacking has increased in the US, there has been comparable increase in carbohydrate consumption over the same time (figure 12). While the ‘quality of food’ (as measured by fat and protein content) has not increased, there was a significant jump in carbohydrate consumption between 1980 and 2000, which links closely to the increase in obesity (figure 13). These are likely to be ‘empty calories’ providing energy without any nutritional benefit. This gives some substance to the theory that the increase in eating frequency, especially processed foods and refined carbs (primarily from snacks) have been a key contributor to the obesity epidemic.

Figure 12: Mean adjusted intakes of macronutrients among adults shown as absolute intake in grams per day (Ford & Dietz, 2013).

Figure 13: Trends in Overweight and Obesity among US Adults (National Institute of Health, 2017)

Research shows that eating more frequently does not reduce hunger (Hutchison & Heilbronn, 2016) and snacking is likely going to only provide you empty calories. But I still wanted to find out if there were any advantages for having even longer gaps between eating.

Benefits of Fasting

Probably the most talked about benefit of fasting is the fact that you can improve your body’s ability to burn fat instead of carbohydrates. Metabolic flexibility is the medical term for the ability of people to switch between carbohydrates and fat as an energy source and is something that many of us have lost in our modern, abundant society.

Every time you eat a meal, especially a meal with carbohydrates, the body preferentially burns carbohydrate as a fuel - carbohydrate oxidation - because it is much easier for the body to burn this glucose than fat. However, the longer you go without eating, in an evolutionary adaptation to maintain glucose in the blood, the body moves to burning more fat - fat oxidation (Wolfe, 1998). Indeed it is well accepted in academia that at the end of an overnight fast, you have moved to burning primarily fat (Kelley, 2005). Compared to our current society, where we seem to eat or snack every couple of hours, by stretching out the time between meals, you are helping train your body to burn fat more effectively.

Additional to the benefit of burning more fat, fasting also reduces the total amount of insulin that your body produces. Insulin is an extremely important hormone that controls the amount of glucose in our blood. The ingestion of carbohydrates (and less strongly protein) stimulates insulin release, which in turn encourages glucose storage and suppresses the release of fats stores in your body (Melzer, 2011). By reducing the frequency of eating, you are reducing the amount of insulin that your body has to produce, keeping your insulin levels low enough to release fat stores for longer.

So it appears there are several advantages to reducing your frequency of eating:

- You will have longer periods with low insulin to help release more of your fat stores

- You will increase the amount of time you will burn fat as energy

However for those of you that have tried fasting before, you will recognize the biggest hurdle to stay on a traditional fasting diet. You will recognize the feeling of your body using all its evolutionary experience to fight back. Our biology has been optimized over millennia to effectively maintain weight and so you may need some tips and tricks to increase your chances of success – even if you have personalized fasting to your preferences.

Working with our own biology

While the energy equation during weight loss is quite simple – Energy in < energy out - in real life being able to maintain that balance is not so simple. Evolutionarily our biology has developed defense mechanisms to ensure our species survives in times of famine. As summarized in the graph below, when calories are restricted by 25%, you are able to reduce body weight and fat mass, but the body responds by reducing our resting energy expenditure and massively increasing hunger to try and limit weight loss (Chaput, Doucet, & Tremblay, 2012)

Figure 14: Percentage of baseline values for resting energy expenditure (REE), body weight, fat mass, hunger and energy intake after 5 d, 2 weeks, 8 weeks and 15 weeks during an ~25% energy intake reduction. Adapted from (Chaput, Doucet, & Tremblay, 2012).

Resting Energy Expenditure

Resting energy expenditure (REE) is much like the name suggests, the energy the body burns when it is sedentary (not moving). This is the energy expended just to run our day-to-day bodily processes including brain function, digestion system as well as all our critical body organs (organ mass makes up only 5–6% of body mass, but accounts for almost 80% of resting energy expenditure).

With a traditional calorie-reduced diet, because your body is constantly exposed to the stress of reduced calories, to maintain equilibrium the body will want to quickly adapt to the ‘new normal’ level of calorie intake. As a response, the most efficient evolutionary option for the body to maintain weight in the face of famine is to reduce energy expenditure and slow the body’s metabolism to match the new calorie intake. The body does this by reducing the amount of energy it expends in the resting state. Dietary restrictions have been shown to reduce REE by 8.4 calories for every lb of weight lost per day (Chaput, Doucet, & Tremblay, 2012). So for a 10lb weight loss, you will need to reduce your calorie intake by nearly 100 calories – the equivalent of a decent snack – just to maintain your energy balance.

Comparatively with fasting, the body is not constantly ‘stressed’ by energy restriction, preventing the body from reaching a comfortable equilibrium (homeostasis), which has advantages for both weight loss and weight management. In one study an increase in REE of ~5% is seen during the first days of fasting (Siervo, et al., 2015). Also a recent trial of alternate-day fasting amongst 26 subjects with obesity, showed REE decreased with traditional reduced-calorie dieting but not with the fasting diet (Catenacci, et al., 2016). It appears that fasting, especially irregular fasting, is one potential strategy to ensure the body does not adapt to reduced calorie intake by dropping REE.

Hunger

Finally, probably the largest challenge that people who have lost weight will acknowledge is the significant increase in feelings of hunger while on a diet. This is the body’s primary and most recognizable response to a calorie-reduced diet. The diet becomes increasingly hard, as you become increasingly hungry. The opportunities and temptation to cheat seem to be everywhere and become irresistible.

Some diets are more difficult than others to maintain and in an analysis of weight loss studies, the dropout rate after 12 months was 38% for low-fat diets and 48% for low carbohydrate diets (Nordmann, et al., 2006). And even when weight is lost, most traditional targeted interventions struggle to sustain their impact, with weight regain ranging from 30-70% of the original loss (figure 1). As is seen in figure 13, feelings of hunger increase by nearly 75% after 15 weeks of being on a 25% calorie restricted diet. No wonder it is so hard to avoid temptation on a restricted calorie diet and the reason people dropout of diets or fail to maintain lost weight.

This is such a big issue when losing weight that it is likely we need support to overcome this increase in hunger. There are some nutritional tricks as well as supplementation tips, including Calocurb that have been proven to help. Supplementation is one of the most exciting recent advances in the science and certainly helped me on my journey to Personalized Fasting.